When I was sojourn-ing at my Father's recently I walked past the most wonderful shop called 'Shamrock Linen' (possibly the dullest website ever can be found here) which is an old-fashion linen shop that sells things made of fabric (as the name implies). Anyway, as I passed the shop I was forced to retrace my steps and look again, as hanging in the window was this...

Cue a flash back to my childhood, the late 70s, and the most unlikely best-selling sensation you can imagine. This is the story of the continuing charm of The Country Diary of the Edwardian Lady...

Who would have guessed in 1977 that the publication of a book of nature notes from over 70 years previously would have caused such a stir. I suppose it could have ridden the wave of nostalgia for the Victorian/Edwardian period that was already happening since the late '60s. Shops like Laura Ashley and Biba, films like Far from the Madding Crowd, Zulu and Tess, plus a host of exhibitions re-evaluating the Victorian art movements made the period cool again, and nostalgia for a time of family values, hard work and a simpler, less threatening ethos was all pervading. I mean, what could provide a stronger antithesis to '70s punk or even the body-conscious, money-loving '80s than Blue Tits in watercolour by a maiden in a long skirt? Enter Edith Holden...

Born in a village just south of Birmingham in 1871, Edith was one of seven children. She and her sister Evelyn showed talent as artists and both worked as illustrators, exhibiting at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists (1890-1907) and the Royal Academy (1907 and 1917).

In 1906, Edith got a job teaching in the Solihull School for Girls and she decided to keep an art diary as a model for her pupils work. This was Nature Notes for 1906, a month by month record of the weather, changes in nature, sightings of birds, flowers and animals, together with delicate watercoloured illustrations of her observations. In addition to this, she inscribed poems and mottos appropriate to the month...

The pleasure of the book is manifold; firstly it is beautiful, really stunning. The illustrations are charming but not twee, precise and loving in their detail. Added to this is the writing - so nice to read someone's actual handwriting in a book. You actually feel you are reading her diary. You can read how on 13th June she gathered figwort and celery-leaved crowfoot and got soaked in a heavy shower of rain, but didn't mind as the weather had been so dry. The verses by poets such as Tennyson, Shelley and William Motherwell are lovely, highlighting the 'art' of the book. What Holden wanted her pupils to appreciate was the beauty of nature through observation and creative interpretation. Looking at it with fresh eyes over thirty years since I first saw it, the Diary is a thing of wonder and delight.

Edith Holden's life is not really known beyond a few moments. We know she married, we know her husband was Ernest Smith, a sculptor who worked for another sculptor, the Countess Feodora Gleichen in London, where Edith moved after her marriage in 1911. After that point she grew somewhat apart form her family and details of her married life are not known, but sadly what we do know is the matter of her death. In 1921, while gathering chestnut buds for sketching, she slipped and fell into the Thames at Kew and drowned, only discovered the day after.

Skip forward to the 1970s and Holden's great niece Rowena Stott published the diary and an industry was born. I remember the bed linen, the tea towels, the crockery, the stationery, everything all covered in delicate flowers and birds and the font of Edith's handwriting...

Edwardian Lady casserole, anyone? This doesn't cover the books, the endless books that took their inspiration from Holden's work...

Possibly the funniest and most predictable of these spin-offs (or cash-ins) has to be this...

Yes, yes, like we didn't see that coming. Mind you, it does echo the original well and is very snigger-some (even if the joke about blue tits is what you would expect. Sigh.)...

Well, that's all well and good for the 1980s, but why was that cushion hanging in Shamrock Linen's window in 2013? Turns out Edith Holden never went away, but that overly busy use of her work on everything was rejected as 'naff and old fashioned' in the rather more minimalist twenty-first century. I admit I had not really thought of her as an inspiration for my home decor as it reminded me of what my parents liked (and not in a good way) and who wants to do what their parents did? Well, maybe they were inspired by the original source material and a return to that is always a positive move. Looking again at The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady is a strange experience as it is so very familiar yet I appreciate it now within the context it was written.

Yes, of course I bought the cushion. It was my 40th birthday, after all.

Cue a flash back to my childhood, the late 70s, and the most unlikely best-selling sensation you can imagine. This is the story of the continuing charm of The Country Diary of the Edwardian Lady...

Who would have guessed in 1977 that the publication of a book of nature notes from over 70 years previously would have caused such a stir. I suppose it could have ridden the wave of nostalgia for the Victorian/Edwardian period that was already happening since the late '60s. Shops like Laura Ashley and Biba, films like Far from the Madding Crowd, Zulu and Tess, plus a host of exhibitions re-evaluating the Victorian art movements made the period cool again, and nostalgia for a time of family values, hard work and a simpler, less threatening ethos was all pervading. I mean, what could provide a stronger antithesis to '70s punk or even the body-conscious, money-loving '80s than Blue Tits in watercolour by a maiden in a long skirt? Enter Edith Holden...

Born in a village just south of Birmingham in 1871, Edith was one of seven children. She and her sister Evelyn showed talent as artists and both worked as illustrators, exhibiting at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists (1890-1907) and the Royal Academy (1907 and 1917).

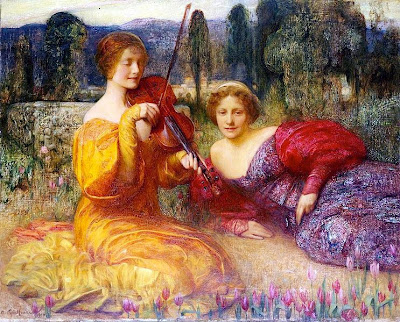

|

| Evelyn Holden's illustrations (unpublished) |

|

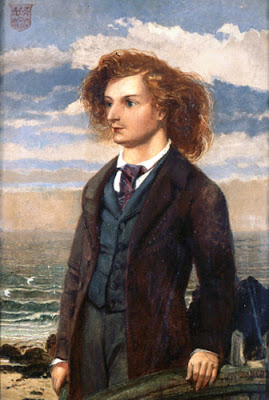

| Edith's illustrations for The Three Goats Gruff by Helen van Cleve Blankmeyer |

|

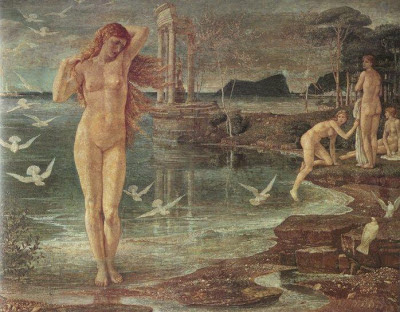

| A page from January's notes |

Edith Holden's life is not really known beyond a few moments. We know she married, we know her husband was Ernest Smith, a sculptor who worked for another sculptor, the Countess Feodora Gleichen in London, where Edith moved after her marriage in 1911. After that point she grew somewhat apart form her family and details of her married life are not known, but sadly what we do know is the matter of her death. In 1921, while gathering chestnut buds for sketching, she slipped and fell into the Thames at Kew and drowned, only discovered the day after.

Skip forward to the 1970s and Holden's great niece Rowena Stott published the diary and an industry was born. I remember the bed linen, the tea towels, the crockery, the stationery, everything all covered in delicate flowers and birds and the font of Edith's handwriting...

Edwardian Lady casserole, anyone? This doesn't cover the books, the endless books that took their inspiration from Holden's work...

|

| I'm quite tempted by this one... |

| This might be a bit '80s for me.... |

Yes, yes, like we didn't see that coming. Mind you, it does echo the original well and is very snigger-some (even if the joke about blue tits is what you would expect. Sigh.)...

Well, that's all well and good for the 1980s, but why was that cushion hanging in Shamrock Linen's window in 2013? Turns out Edith Holden never went away, but that overly busy use of her work on everything was rejected as 'naff and old fashioned' in the rather more minimalist twenty-first century. I admit I had not really thought of her as an inspiration for my home decor as it reminded me of what my parents liked (and not in a good way) and who wants to do what their parents did? Well, maybe they were inspired by the original source material and a return to that is always a positive move. Looking again at The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady is a strange experience as it is so very familiar yet I appreciate it now within the context it was written.

Yes, of course I bought the cushion. It was my 40th birthday, after all.

_c.1913.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

+++Agnes+Poynter+1867+(2).jpg)

.gif)

.jpg)