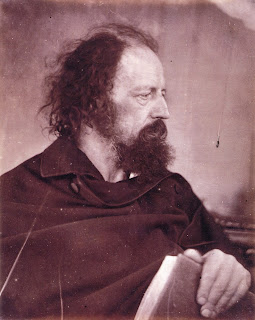

As we saw from the previous post, the way that Julia Margaret Cameron chose to dress her subjects ranged from the simplicity of swathes of white or black robes to elaborate patterned dresses, and this approach also extended to her use of jewellery. In her collection, Julia held pieces in Indian silver, crowns, and Celtic brooches and clasps that decorated the shoulder, chests, heads, and necks of the women in her art.

![]() |

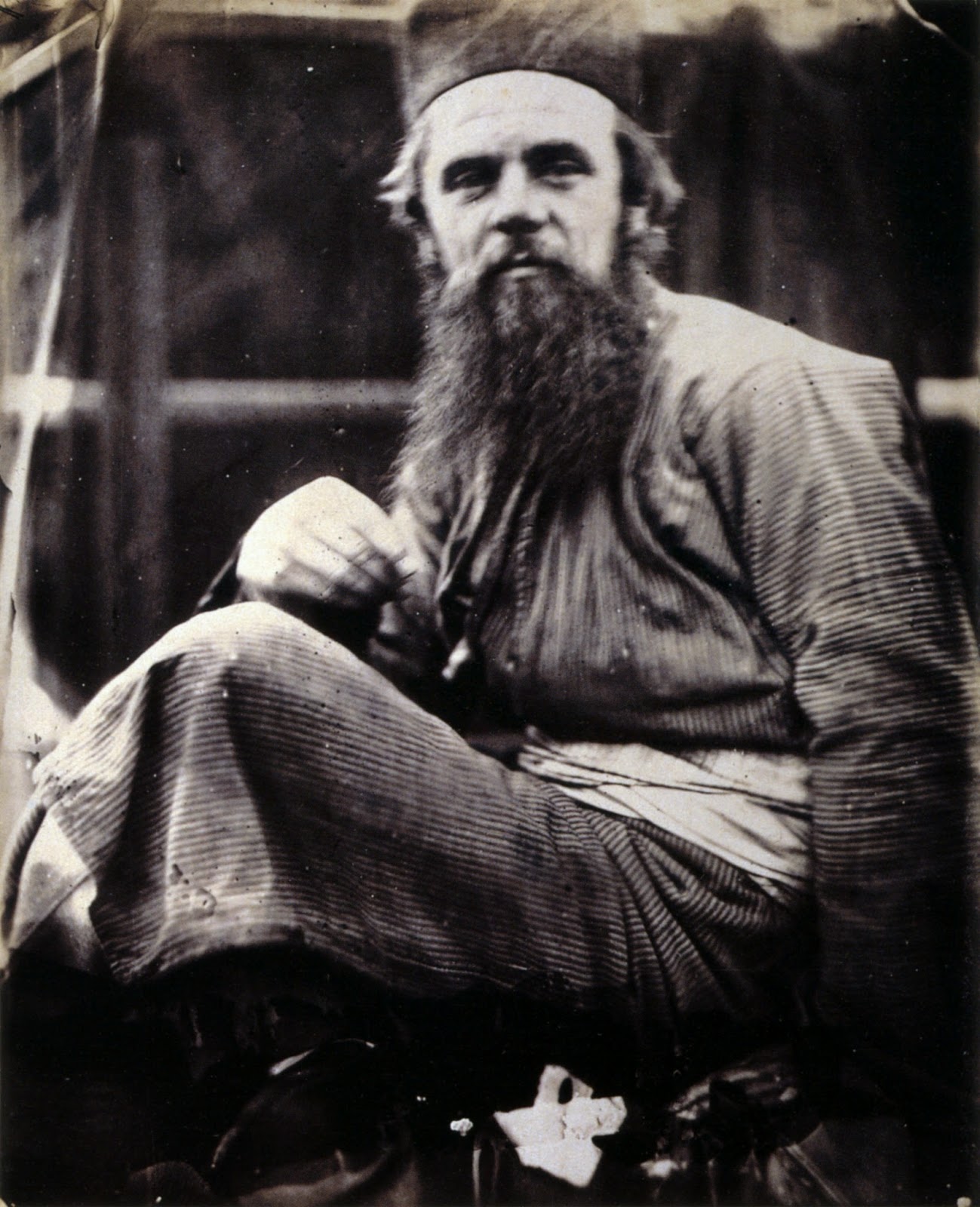

| Julia Margaret Cameron (1859) Lewis Carroll |

![]() |

| Detail of her brooch in the above picture |

Starting with Julia's own image again, I was struck by her penannular brooch, a beautiful mock-Celtic 'Tara' style fastening. These became popular in the mid-nineteenth century when the Celtic Revival took inspiration from the pins displayed at the Great Industrial Exhibition in Dublin in 1853. Before long, cheaper Indian silver replicas were available at a fraction of the amount charged by Irish craftsmen. It is apparent that Julia owned a couple if not more of these Celtic-style brooches and used them to pin the drapery in her photographs.

![]() |

| Yes or No (1865) |

![]() |

| Eleanor Campbell (1868) |

![]() |

| Julia Margaret Cameron and her watches (1858) Unknown Photographer |

The Celtic-style brooch was not the only type displayed; Kate Keown, in the centre of

The Minstrels group, wore a round brooch which reminds me of a piece designed by William Morris.

![]() |

| Minstrel Group (1866) |

![]() |

| Detail of the brooch |

The shield brooch appears again in

Mignon, a picture taken at the same session as the above image. Both penannular and shield brooches are very distinctive and their positioning in the centre of the garment makes them easy to recognise and act as shorthand for past ages as well as current fashion.

A far more ostentatious way of 'bejewelling' models was in the use of elaborate necklaces, such as this example, which appears to have a chain of the Star of David in fine silver...

![]() |

| A Holy Family (1872) |

The necklace has been pinned along the front of the neckline and I thought it was part of the dress until I saw the same necklace worn again in

Balaustion...

![]() |

| Balaustion (1871) |

It is possible to 'chase' items of jewellery from one image to another. In the case of the headband in

Balaustion, it occurs again as a necklace in

Hark! Hark!![]() |

| Hark! Hark! (c.1870) |

The square necklace in

Zenobia becomes a bracelet (just seen around her left wrist) in

Mariana...

![]() |

| Zenobia (1870) |

![]() |

| Mariana (1874-75) |

And Mary Hillier wears the same disc necklace that she wore in

Sappho in other less specific portraits of her...

![]() |

| Mary Hillier (1864-65) |

![]() |

Sappho (1865)

|

In terms of modern portraits or scenes, Julia seems to have employed strings of pearls, either belonging to the sitter or owned herself, giving a decorative but timeless quality...

![]() |

| Anne Thackeray Richie (Lady Richie) (1870) |

Lady Richie was a family friend and sat for this light-infused portrait as well as the one from the previous post. Her pearls are little dots of light in a shimmering composition, in complete contrast to the darker picture with her nieces. The pearls, both here and in other works such as

For He Will See Them On Tonight stand for understated opulence and luxury steeped in purity. Another instance of pearls occurs in the Tennyson inspired

And Enid Sang...

![]() |

| And Enid Sang (1874) |

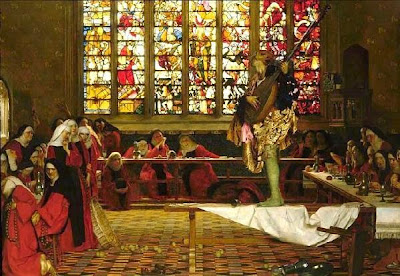

Often linked with Dante Gabriel Rossetti's works such as

A Christmas Carol (left) or

Joli Coeur,

And Enid Sang uses the familiar template of a beautiful, loose-haired woman playing an instrument, the hearts on her jewellery showing the world her love. Emily Peacock as Enid plays the part of the Tennysonian heroine, lover of the knight Geraint. The look of melancholy seems to contradict the hearts around her neck but reflects the sorrow that Enid suffered in her loyalty to her beloved Geraint, a passive victim of both Fortune (as expressed in her song) and her husband's jealousy. Still through it all she has enough love to see her through, as expressed by the many shiny hearts around her necklace.

![]() |

| Sadness (1864) |

While we're on the subject of unhappy lovers, it seems appropriate to move to this picture. Taken at Farringford, while G F Watts and his young bride were on honeymoon, it seems an odd choice to pose as the epitome of sadness. Ellen Terry looks terribly woebegone, but you could argue that as an actress, she was just playing a part for a picture. I did wonder at the link to this picture though...

![]() |

| Choosing (1864) G F Watts |

Ellen is shown in this wedding portrait, holding the scented violets in her hand while sniffing the showy, unscented camellias. Over the top of her wedding dress's lace collar is a string of beads, possibly the same ones she wears in

Sadness. I also think the bangles she wears in both picture are the same, possibly linking the notion of sorrow to her marriage, which would have been unfortunately apt.

Moving up, Julia literally 'crowned' a lot of her subjects with coronets and jewels that glimmer among the tumbling hair.

![]() |

| A Bacchante (1867) |

![]() |

| Vectis (1868) |

In both

A Bacchante and

Vectis, Cyllena Wilson wears tiny pins in her hair, some in the shape of stars. Unusually, these are the only jewellery worn in both images, making them stand out of the otherwise unadorned images, the stars especially striking in their beauty.

![]() |

| The Return After Three Days (1865) |

In both the above image and

Trust Mary Hillier has a round brooch pinned to the scarf in her hair, adding a glimmer to the dark mass of her hair and headscarf. Similarly, the crescent that tops the outfit of the following woman gives her a mystical, goddess quality...

![]() |

| Unknown Woman (1864-66) |

Possibly the most amazing of the pieces of jewellery worn are the crowns and coronets that grace the heads of Julia's muses. These range from simple bands to more elaborate, jewel-encrusted pieces.

![]() |

King Ahasuerus and Queen Esther (1865)

|

![]() |

| Mary Hillier (1864-65) |

Henry Taylor wears a pointed crown and Mary Ryan has a jewelled band that can also be seen on Mary Hillier's head in her portrait of 1864-65. Taylor can be seen in his pointy crown as King David as well.

![]() |

| Study of King David (1865-66) |

A very elaborate crown can be seen on Mary Hillier's head in this photograph of 1864-66...

![]() |

| Mary Hillier (1864-66) |

That is probably the biggest of Julia's crowns, making Mary look majestic and formal rather than the rounded maternal figure she normally portrayed. It isn't Mary's only crown moment though, she also wears a jewel-set curved one in The Holy Family, possibly the same one worn by Alice Liddell in St Agnes.

![]() |

| The Holy Family (1872) |

![]() |

| St Agnes (1872) |

The full extent to Julia's costume box can be seen in The Passing of Arthur, with three crowns on display...

![]() |

| The Passing of Arthur (1874) |

Possibly taking Daniel Maclise's illustration of the death of King Arthur from the Moxon Tennyson as inspiration,

The Passing of Arthur has three handmaidens, each wearing a crown. The middle and left-hand crowns are little more than bands with small details. The middle crown with the little balls along the top reoccurs on the head of Lorina Liddell in

King Lear...

![]() |

| King Lear Allotting His Kingdom to his Three Daughters (1872) |

I find the differences in costume between the men and women in Julia's work very interesting and crowns are a good measure of her attitudes towards both. Possibly the difference in age between the majority of her male and female sitters can be seen as an indication of how she saw ideal male/female dynamic - the men, like her husband, older and wiser, the women young and patient, knowing their place (the exception being Vivien and Merlin, obviously).

![]() |

| Queen Philipa Interceding for the Burghers of Calais (1872-74) |

Queen Philipa is a very obvious example of the dynamic. The noble queen, wearing a thin band of a crown, pleads for justice for the people of Calais and the burghers who have come to broker peace. King Edward, wearing the same crown as King David above but with stars attached, listens to the wise counsel of his young wife. In marrying a much older man herself, possibly this is how Julia saw the ideal, although it can hardly be said that the marvellously bossy photographer fits the type of one of her patient, passive women.

![]() |

| Zoe (1870) |

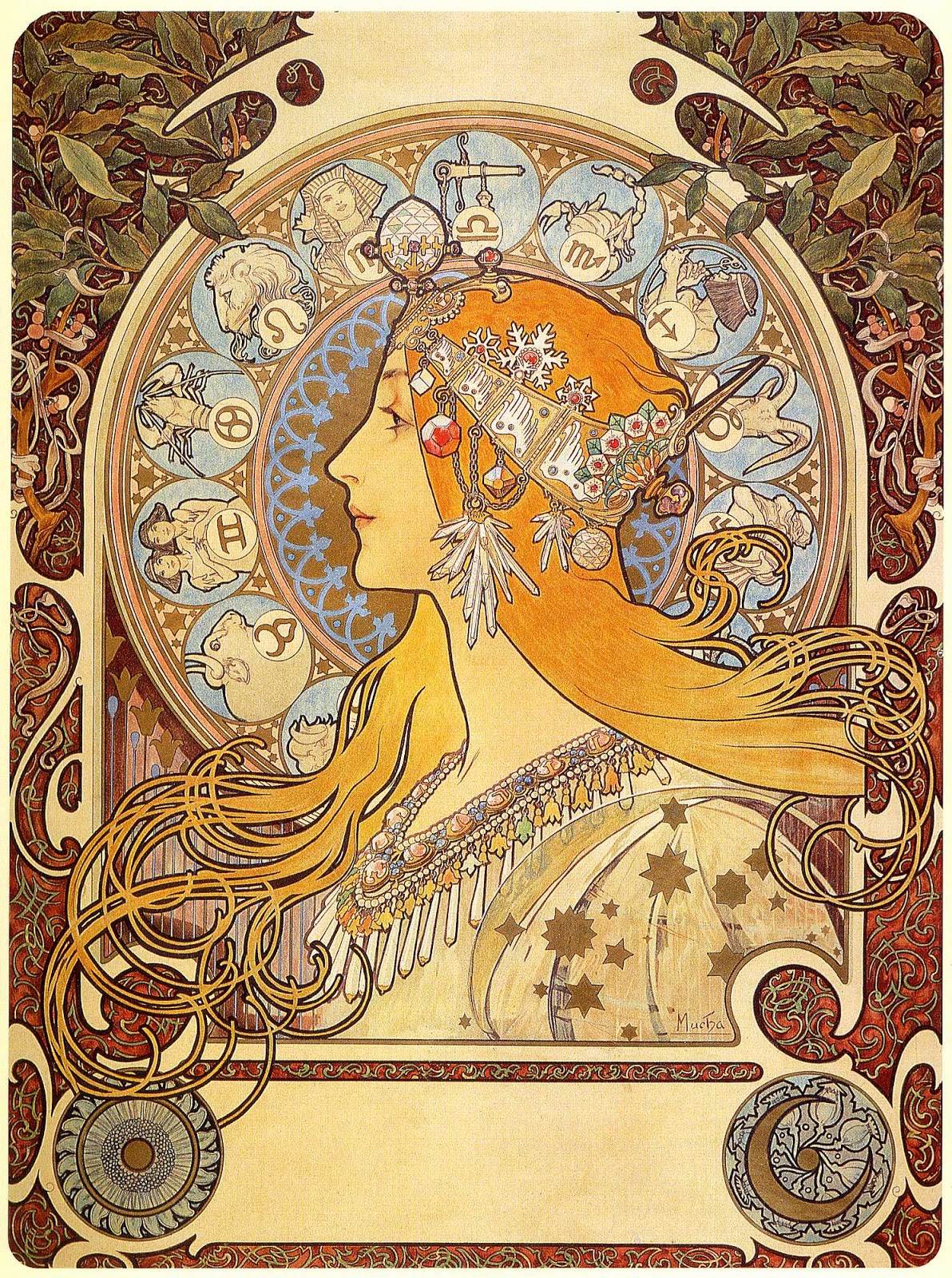

I have really enjoyed searching through Julia's photographs, matching the garments and jewellery of her costumes. Through her use of ornamentation, Julia shares Rossetti's vision of ornamented women, garlanded with jewels, making their bodies decorative surfaces to add meaning to the whole. Something in the ingenious placing of pieces, necklaces to headdresses for example, promotes the exotic in her work, reflecting that part of her art which was forever rooted in the colonies, away from a traditional Victorian aesthetic. It is this part that shows us her vision of making a fantasy land in the back garden of a house in Freshwater.

Happy birthday, Julia Margaret Cameron!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg)

_by_Julia_Margaret_Cameron_1874.jpg)

_by_William_Prinsep_1838.jpg)

_1866_by_Julia_Margaret_Cameron.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)